Imagine a city filled with hundreds of fanciful sculptures, some as tall as buildings, each unique, all designed to burn. For five days and nights the people celebrate, taking to the car-free streets in elaborate costumes, accompanied by a cacophony of music and the near-constant detonation of fireworks. At the end of the week, the sculptures are all put to the torch in a single night of fiery destruction, and the next morning no physical trace of the celebration can be found.

Sound familiar?

The place I’m describing is not Black Rock City. It’s Valencia, on the Mediterranean coast of Spain. And its signature celebration, Las Fallas, has been going on for centuries, not decades.

It’s become something of a cliché for journalists to ask us if our event was inspired by the Wicker Man, or Zozobra, or some other older tradition involving burning human figures. And there’s always a trace of disappointment, even skepticism, when they learn that the idea for Burning Man arose independently in the imagination of Mister Harvey. Still, it’s clear that culture doesn’t occur in a vacuum, and that every good idea has an echo somewhere in the world. Back in my Cacophony Society days, we used to have a section in the newsletter called “Sounds like Cacophony.” In that sense, Las Fallas definitely sounds like Burning Man. And when the wind blows a certain way, filled with pyro smoke, it smells like it too.

The similarities run deep and wide. Las Fallas is a grass-roots community event, powered by close to 400 neighborhood Falla associations that are roughly analogous to our Theme Camps. That is, if Theme Camps worked together year-round, collected monthly dues, and funded the majority of the city’s art, with only a quarter of the costs offset by public funds. Most crews fund two installations, a principal falla and a smaller children’s falla, which adds up to nearly 800 artist commissions for the festival.

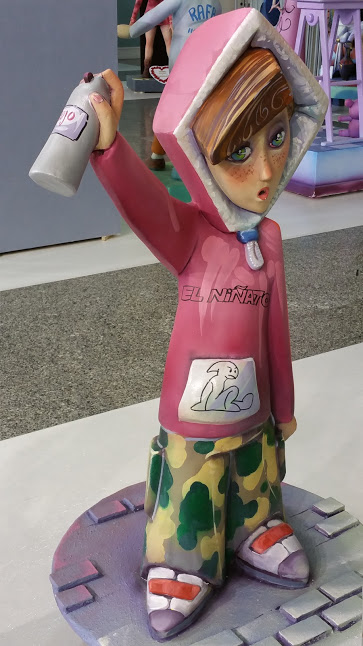

Thematically, there is a long-running tradition among the falla artists of poking fun at the powerful, with satirical barbs leveled at politicians, bankers, and everyday idiocy. These unflattering caricatures often involve sly double-entendres and ribald sexuality, which may explain why the tradition has endured through periods of extreme political repression. Historians point out that Franco not only allowed Fallas to exist, but in a rare exception to policy allowed them to use the Valencian language in the festival, when other non-Castilian languages were being officially squashed. A local expert explained that since the fallas are so cartoonish, any attempt to ban them would have made the dictator look petty and ridiculous.

While many fallas are thematically edgy, at a stylistic level there is a remarkable degree of conformity, with most of the sculptures executed in a style that can only be described as Disneyesque. Part of this may have to do with the dominant construction method, which involves sculpted Styrofoam over a light wooden frame, smoothed and airbrushed, which makes it possible to create incredibly detailed 3-D cartoons (yes, they burn foam — more on that later). There are historical roots for the tradition as well: take a walk through the Fallas Museum and you’ll see the influence of American pop culture going back as far as the back as the early 1950s, with fallas specifically modeled on themes from Disney, Warner Brothers, and Hanna-Barbera.

But not all falla artists are content to replay endless variations on mass-culture imagery. There is a growing movement that’s far more experimental, both thematically and in the use of alternative materials. This year’s municipal falla, the one financed by the city and placed prominently in the town square opposite City Hall, represented a stark contrast to all those cartoon princes and princesses. Designed and built by esteemed falla artist Manolo Garcia, it was a 20-meter stylized human figure built entirely of wood. Other artists like David Moreno and Miguel Arraiz are experimenting with new looks and newer, greener-burning materials such as wood and cardboard in their fallas, creating modernist and sometimes abstract forms that transcend the cartoon motif.

In 2015 we invited David and Miguel to Black Rock City, and they returned home convinced that our two cities have a lot in common and much to learn from each other. In March of this year, the Valencians reciprocated with an invitation of their own, and the Burning Man Arts team arranged to send three Burners to Valencia in an exchange project: artists Karen Cusolito and Arlo Laibowitz, and pyrotechnician Dave X. In a parallel co-learning effort, Crimson Rose and I were invited to speak about Burning Man at the Modern Art Institute, and the city government arranged a series of formal and informal meetings with the mayor and his staff. The Burner delegation was received with open arms by the community, and we were able to engage with a wide range of artist groups, falla associations, and event organizers in both the public and private spheres. And yes, we ate a LOT of paella.

So why would a major European city with a centuries-old festival tradition be interested in Burning Man? At the artistic level, as I’ve said, there is a growing interest in creative revitalization and shifting to new materials. At the city level, the newly elected administration of mayor Joan Ribo is shaking things up after twenty years of conservative rule. Elected on a center-left, strongly environmentalist platform, the new leadership sees Burning Man as a source of fresh thinking and new practices for making their event greener and more radically inclusive.

As a Burning Man representative, I was interested in how the Valencians have managed to create such an enduring tradition. In the fallas halls, I experienced their multi-generational culture firsthand, and saw how the children are deeply involved and engaged as participants. In our discussions with the city, we learned about the nuances of a successful public-private cooperation, including their co-funding structure. We discovered that the festival is not universally loved by the citizens, and that many in fact leave town for the week to get away from the noise and traffic. But the numbers are hard to argue with: the city invests something like 8 million euros each year in grants and public services to support Las Fallas, and the economic return from the free-admission event is estimated to be as high as 800 million.

As an unexpected bonus, we learned about Valencia’s vibrant street art culture. Not surprisingly, some of the younger and bolder falla artists create public art in the off-season through events like the Intramurs festival, where the city is basically handed over to street artists for a week. Our friends David and Miguel are active in both circles, along with people like Escif, a celebrated Valenciano street artist who worked with Banksy on the Dismaland project, and whose falla project last year was a pair of realistic-looking, illegally-parked cars fashioned from wood.

David and Miguel, along with a posse of Valencianos, will be bringing an art project to the Playa this year as Honorarium grantees. Interestingly, they do not plan to burn their installation in BRC, but instead plan to pack it up and return it to the streets of Valencia, to be burned in November for the Intramurs event. And so the circle of exchange continues between two communities on opposite sides of the world, linked by a shared passion for art, fire, and celebration.

Big thanks to Christian Garcia Almenár for helping to make this project happen

Photos by Stuart Mangrum