You want to get excited about your pilgrimage to the playa? Attend the Desert Arts Preview. The low-key event, held on June 11 in San Francisco, offered an opportunity for 16 artists to share what they’ve been working on for Burning Man 2017 and do a callout for last-minute help and supplies. While 16 is but a sliver of the 300+ artworks that will be scattered about Black Rock City this year, the preview did showcase some of the biggest and most ambitious projects coming to life. (Artists kept trying to one-up each other, playfully, when it came to the height of their sculptures. Reared in Steel’s Flower Tower won, at 70’ tall.)

There’s no question about it: The art feels special this year — and it’s not just the four-story jellyfish made up of over 2,000 mini jellies, the flamingo the size of a T-Rex, or the Gummy Bear pyramid. There’s also an organic, arboreal theme uniting several installations, in the form of trees, a forest, and special sources of wood. Beyond the wow factor of these pieces, there is the true strength, sober beauty, undeniable life force of trees and humans’ tenuous relationship to them. We learned about four major pieces that have their roots (wink) here.

Tree of Ténéré

A huge, verdant, life-like tree in the middle of the desert… that can support 60 climbers… with hand-painted bark that looks impossibly real… and 175,000 LEDs on 25,000 leaves… with color that can change 200 times per second… powered by 208 microprocessors… allowing for the animation of breathtaking patterns, shapes and colors that respond to music, voices and biorhythms. It had us at “tree in the desert”, but we’ll take the largest interactive light canvas in the world. Meet Tree of Ténéré.

Led by Alex Green, Mark Slee, Zachary Smith, and Patrick Deegan, the piece is named after a tree that once grew in the Ténéré region of the Sahara desert. It was considered the most isolated tree on Earth. You could go 250 miles in any direction and not find another living thing. Yet somehow this lone tree managed to survive. In fact, it became a landmark — a “living lighthouse” — for desert traders and travelers. They used to meet beneath the tree during their desert crossing for rituals and rest.

“After a week in the barren desert, I think a lot of people start to feel a void and crave natural beauty like trees, flowers, and bodies of water,” says Smith. “It’s no surprise that artists want to play with this void, and use it as an opportunity to decontextualize natural objects and forms.”

Play with the void — and invite others to engage, too. The Ténéré team have open-sourced the control software so artists and technologists around the world can dream up light shows and interactive experiences for this new medium. And every night at 10 pm there will be a live performance beneath the tree. Think fire dancers, aerial performers, opera singers and string quintets whose music will animate the leaves.

“We fell in love with the idea that a simple tree can become an almost sacred space in the right environment,” explains Smith. “What more perfect place than Black Rock City to bring the spirit of this tree back to life?”

A note from the team: “We’re still looking for some generous donors to help fund the completion of the tree. We’re very close!” Please reach out to zacharyvsmith@gmail.com if interested helping out.

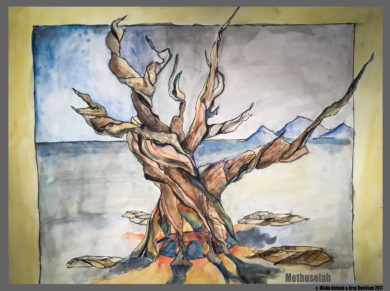

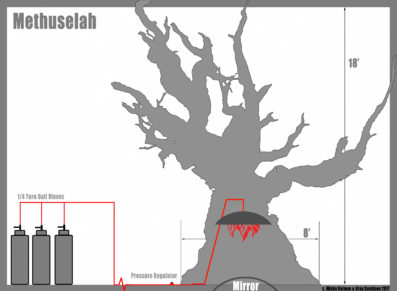

Methuselah

Methuselah is an ancient tree that serves as an icon of remembrance and ancestry, but the sculpture derives its inspiration from the tree Ygddrasil, the world tree from Nordic mythology.

“Ancestry and evolution are key themes for our work,” says Misha Naiman, who’s leading the project with Gray Davidson. “Methuselah’s rings and branches bore witness to the entire span of recorded human history. Great trees gave their limbs and leaves as axles, paper, bows, hulls and roofs, and held space and time for our ancestors’ radical rituals.”

The tree is made from Great Basin Bristlecone Pine, which grows in isolated places with no rainfall and terrible soil. (Sound familiar?) According to Naiman, they are difficult to cultivate, and humans haven’t been able to hybridize them. “I love the wildness of these trees,” she says, “and wanted to bring that out to the desert.”

The heart of the tree will contain a flame effect, and inside the trunk will be small welded messages, runic symbols, and tiles made by loved ones. (Each member of the crew is encouraged to think of something meaningful to put inside the tree.) One of the low-hanging branches will support aerial and shibari performances throughout the week.

Says Naiman: “We hope that Methuselah will act as an invitation for participants to disengage from the frenzy of present day time, anchoring them in the still time of mythology.”

Methuselah is still fundraising. You can contribute to this project via Indiegogo.

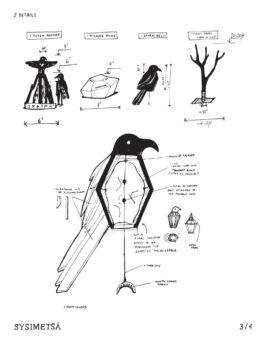

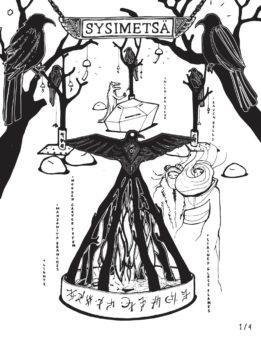

Sysimetsä

This is a story about coming up from the ashes — literally.

In 2015, the Rocky Fire burned down LaynaJoy Rivas’ art studio and a quarter of her land, not to mention huge swaths of Lake County where she lives. To rebuild, she salvaged the dead forest, debarking and preserving trees to use as timber frames. And that’s when it hit her: “Burnt trees are beautiful. Let’s bring a burnt forest to the playa.”

A Finnish word for “wild woods,” Sysimetsä is Rivas’ first work of art for the playa. (She’s building it with her partner, Izek, and other dear friends, like Eva Reiska, who’ve helped her rebuild her art space and The Landing Ravens, their art collective’s home.) Her forest will consist of seven real burnt trees mounted on metal plates, spread out over 50-60 feet. Inside the trees will be ravens, made from manzanita branches, with bells that participants can ring.

At the center of the forest will be a memorial to the fire and the beauty of the forest — a totem made out of manzanita branches, salvaged wood from a past Burn (Rivas was on the Man build team), and a huge piece of oak from another burned tree that’s been carved into a raven. Glass flames will glow from underneath the totem, like a bonfire, and at night there will pulse a light like a beating heart.

“People are very desensitized from destruction and disaster, so this is a really intense way to be like, here, experience it firsthand. Not a lot of people get the opportunity to walk through a burnt forest,” Rivas explains.

These trees she used will never come back, she assures, as she waited the requisite time to ensure that they didn’t start growing again. All the trees being salvaged are cut, debarked to protect against MOOP, then re-burned and shellacked. Everything was done off-grid in a sustainable manner.

The wild woods will rise again.

Sysimetsä is still looking for funds (for tools). You can contribute via their GoFundMe page and follow the project on Facebook.

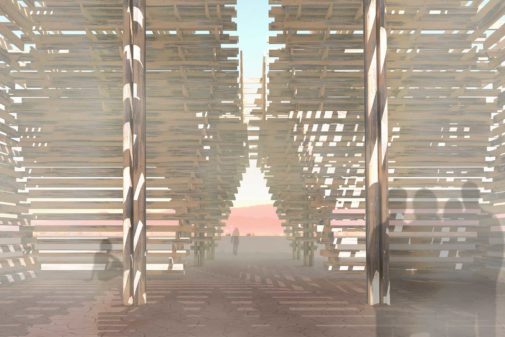

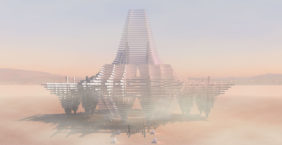

The Temple

It’s safe to assume that The Temple is going to be a stunning, spiritual structure. But what the average participant may not have pondered are the materials that make up the thing — it’s just wood, right?

Not this year. For the first time ever, the Temple’s lumber is coming from an unexpected place with an urgent message about conservation: It will be made from 2,000 pieces of dead wood that had been destroyed by the pine bark beetle in the Sierra Foothills. The ecology page of The Temple site notes that all of the Western U.S. states are experiencing elevated levels of forest decline from diseases like Sudden Oak Death and pine bark beetles. And it’s not just from climate change, says Lee Klinger, the scientist who wrote the explanatory page. Other human activities have contributed to the declining state of our forests, creating a precarious situation that’s top of mind for The Temple crew.

“Due to climate change, the drought and poor forest management policies, there are millions of dead trees right now in forests across the United States. These dead trees are like a tinder box, and are greatly contributing to the risk of forest fire,” explains Marisha Farnsworth, a core member of the team.

“Sadly, there is little economic incentive to remove these trees from our forests,” she continues. “We are hoping The Temple will help spread the word about the state of our forests and to encourage other people to find uses for these trees before they rot.”

Ironically, it is our own fire suppression practices that have contributed to the pine bark beetle epidemic, says Farnsworth, adding that controlled burns can help keep this native pest at bay. “People are slowly recognizing the benefits of controlled burns,” she observes. “We thought this was a great subtext for The Temple since the ritual of fire is so central to the Burning Man event.”

“For me, this temple will be for the trees!” says Klinger.

Sounds like he won’t be alone.

The Temple crew is still fundraising. You can donate here if you’d like to help them out.

Hey, our honorarium project, “Margareta Appalachia”, will also feature trees!

The interior space of the 22′ tall woman (hoisting a peace sign) will include an installation evoking a rainforest from the Carboniferous Period (320 million years ago), which are the plants which gave rise to the Appalachian coal fields. Although technically, these plants were ancient forms such as tree ferns and lepidodendrons!

Plus the coal incorporated into the piece are technically trees! And the verdant hills in front of the woman devolve into flat-topped platforms behind her, symbolizing the industrial process of strip-mining which causes deforestation (among other problems).

Hooray for the year of the tree!

Report comment

Also, David Boyer’s wind-driven sculpture “Macchina Naturale” is designed to be tree-like too!

https://burningman.org/event/brc/2017-art-installations/?yyyy=&artType=H#a2Id0000001IR1QEAW

Report comment

Yay for the trees!!! As a full-time metal sculptor of trees, I am so excited to see these trees out at BRC! Trees have such a magical essence that for me is “temple” like. So perfect, I think, for this years’ theme :)

Report comment

Trying to reach Mia after reading her article about Camp Aging Insurrection.

How do i contact that camp to see if they have room?

Report comment

Hi Roxbury! Let me see if they are going this year and best way to contact. Be right back!

Report comment

Comments are closed.