Part of a series about 2017 National Week of Making.

They don’t call it Artisan’s Asylum for nuffin. The 40,000 square foot makerspace in Somerville, Massachusetts, is a mixture of mad science and a dizzying array of tools, skills, inmates and projects.

It’s the kind of space that enabled one man’s dream to run local robot fights. It also provided a platform for Asylum’s founder Gui Cavalcanti to eventually establish a start-up in Oakland called Megabots and to challenge Japan to a giant robot-off in August 2017.

There are 400 members, 170 studios and artisans that range from a bloke building period furniture with period hand tools to an artist whose vending machine churned out thousands of 3D-printed roosters in Boston’s Chinatown Park to mark the Chinese New Year and the Year of the Rooster.

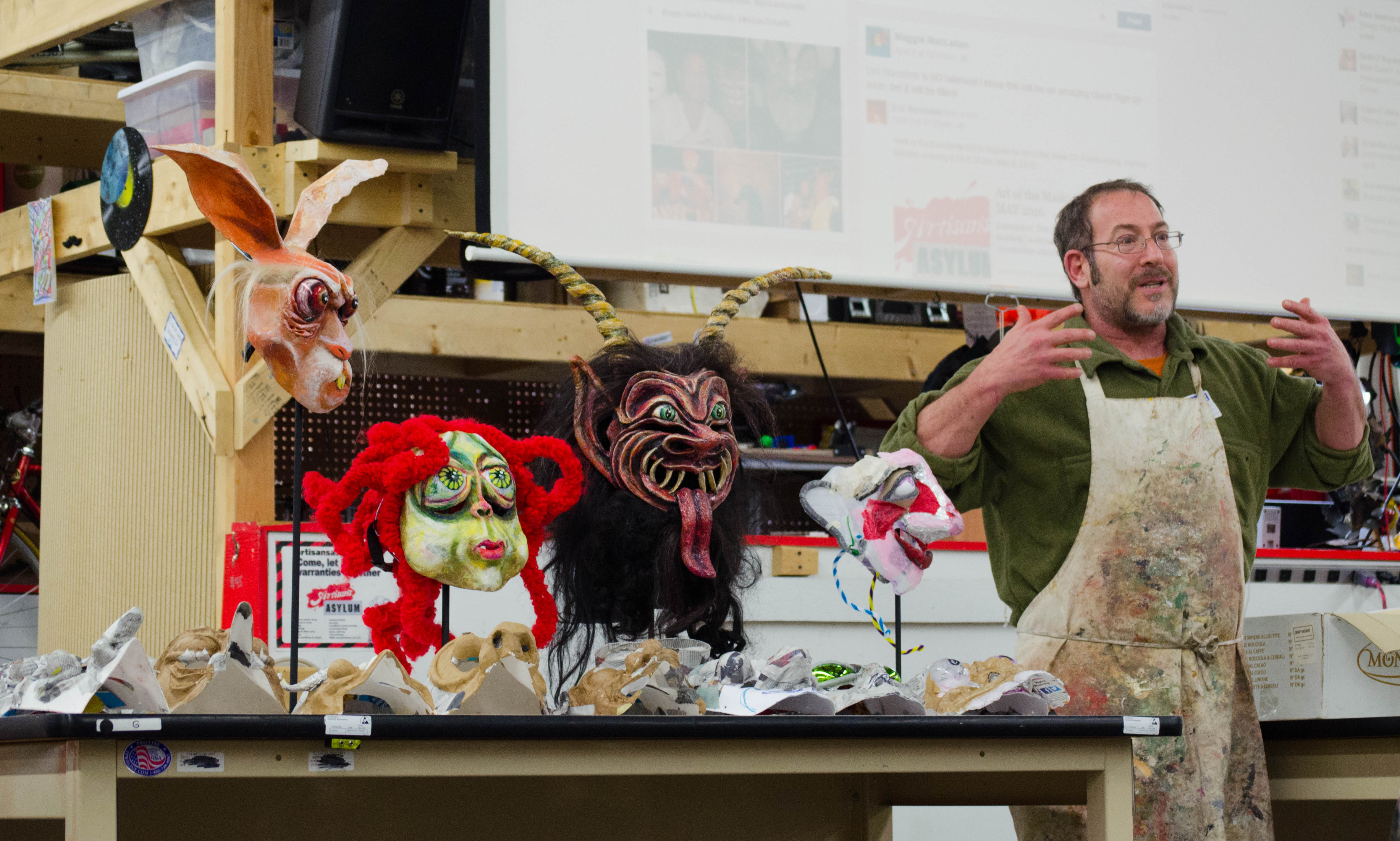

The Asylum’s communal workshop spaces also support woodworking; metal machining, welding and fabrication; 3D printing, electronics and robotics; jewelry and metal casting; screen printing; a bike shop; and costume and prop making.

Top that off with tours, training, outreach programs, conferences, exchange programs and internal art grants, and I don’t know about you, but I suddenly feel like that mythical post-coital cigarette.

But Artisan’s Asylum is more than a maker’s wet dream; it broke new ground and paved the way for other maker spaces to emerge in Boston and beyond.

How it All Started

Derek Seabury, the president of Artisan’s Asylum, says it all began with robot fiend Gui and his partner, Jenn Martinez, who was a costumier. The couple dreamed of having access to mills and machines, and so in 2010 put the call out on Facebook: “Who would like to share some tools?”

“They had 100 people turn up for the organizing meeting, and they were an interesting mix of engineers and creative and blues dancers. It brought out a really kinda cool community,” says Derek.

“And when it took off, they were really very aspirational. They tried to draw on the Principles from Burning Man. A lot of the original folks were big Burners, and they were trying to bring the spirit of the event to the outside world in a collaborative, creative community,” he says.

According to Derek, this groundswell of interest was also indicative of a greater need for affordable workspace and the time was right for the genesis of Artisan’s Asylum.

After establishing themselves in two smaller studio spaces, the Artisan’s Asylum moved to its current location at the AMES envelope factor in 2011. The collective started with 20,000 square feet but quickly filled it and expanded to the 40,000 square feet they now inhabit.

“We were like, ‘how will we ever fill that?’” Derek remembers. “But so many people needed a place to work.”

Growing Pains

But the evolution of the space was far from smooth. At a time when makerspaces were not widely known, Artisan’s Asylum faced perplexed and, at times, resistant building owners, banks and insurance brokers who didn’t understand what they were trying to do.

“Some of the initial challenges included finding people to cosign a loan for us, to make that first rent payment. There were a lot of people with a lot of faith in the concept and they really invested their credibility and their credit to make it possible. Even the buildings…”You want to do what here!?” says Derek.

When the Artisan’s Asylum applied to become a nonprofit in 2012, they also met resistance.

“Nowadays it’s a lot easier for a makerspace to become a nonprofit. But we were initially rejected, and we went back and fought it out to make the case. They didn’t see it as an educational resources: they saw it as a club,” he says.

“Trying to become a registered nonprofit was really trying to explain how this was a community benefit and how the creation of physical objects was really an important means of human expression and our history.”

And while Derek is loathe to focus on the economics, he also points out that makerspaces like Artisan’s Asylum have an important role to play in enabling the growth of the creative economy.

“I almost never like to talk about the economic impact that this place has because that’s not how I want to curate it, but at the same time you see a lot of economic development projects, including a maker space, trying to draw in and support the creative community and creative industry,” he says.

Sharing Their Lessons

Outreach continues to be an important part of Artisan’s Asylum as they share their experiences and learnings with others.

“This is only a useful space if you can get yourself and your project here, so if you’re not nearby, the best we can do is help you start your own,” he says. “We did a ‘How to make a maker space’ conference in 2013, and we’ve probably had about 50 of those people go on to create maker spaces where they are.”

Their lessons extend to the tools they keep, with public workshops on offer for every imaginable machine and skillset. Artisan’s Asylum also recently welcomed back one of its members from Thailand Makerspace, where he learned traditional woodworking skills as part of the Asylum’s Makerspace Exchange Residency program. He’s sharing those skills in an upcoming public workshop.

The Existence of Making

More than anything, Artisan’s Asylum is a community that is eager to support each other and share their making joy.

“Whether you’re doing projection art on the side of a wall or you’re working in bronze that could survive the ages, there are a lot of people here trying to create representations of their existence, share that feeling and inspire others,” says Derek.

According to him, making has often been a fundamental acting of defining existence.

“Sometimes the creation of a physical thing is the way we come to exist and be aware of that existence — ever since we started painting on the cave walls to carving ‘Derek was here’ on a picnic table to whatever comes next,” says Derek.

“Making is not necessarily for everyone, but if there’s an itch in the back of mind, maybe it’s that thing trying to get out and maybe there’s something in you that the world needs to have. And we’re here to help you get it out with tools and, more importantly, a bunch of people who are excited to find out what it is.”

Photos courtesy of Artisan’s Asylum