Part of the Art, Money, and the Renaissance blog series

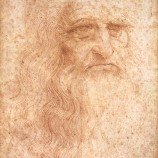

Silicon Valley didn’t invent the “gig economy.” On the contrary, the life of a contractor with neither benefits nor security would have been very familiar to Leonardo da Vinci.

According to Dr. Matthew Landrus, a member of the history faculty at Oxford and a specialist on the artists and engineers of the 14th-18th centuries, Leonardo was a “working artist” with frequent commissions, yes, but he made most of his money from civil and military engineering. And if he was constantly in demand, it was because “he worked hard to make sure he was in demand.”

In fact, of the voluminous journals that Leonardo left us, including his thoughts on art, engineering, science, nature, history, and even (up to a point) social customs — there is virtually nothing indicating his political views.

“That was too dangerous,” Landrus said. “He didn’t want to risk offending a patron.” Leonardo was a celebrity, he was a legend in his own time, but he didn’t have a safety net. There was no plan B.

The “gig economy” (or “service economy” if you want a less accurate euphemism) is not an innovation but a recurrence of an earlier model and an earlier time. Artists have usually lived on the economic fringes of society, but for most of Western history everyone was, in some way, dependent upon the largesse of a patron.

It was the rise of the middle class — the very bourgeoisie whom 20th century artists delighted in mocking and shocking — that made the idea of an independent citizenry possible. The “nation of shopkeepers” were what made an independent avant garde a force.

But if economic forces were vital for art’s liberation from patronage, it still didn’t happen by accident. The man who is most often credited for freeing artists from the patronage system lived almost 300 years after Leonardo, and it’s a story every artist should know.

Dr. Samuel Johnson wrote the first full dictionary of the English language, and when he began the project, it was under the patronage of the 4th Earl of Chesterfield. But after providing an initial grant, Chesterfield stopped supporting it for the entirety of the seven years it took Johnson to finish. After it was done, however, Chesterfield began mentioning the Dictionary publicly, along with his own “involvement” in the project.

Johnson, notoriously easy to offend, responded with a public letter in which he trashed Chesterfield — and the idea of patrons as a whole.

“Is not a patron, my lord, one who looks with unconcern on a man struggling for life in the water, and when he has reached ground, encumbers him with help?” Johnson wrote.

This letter, now infamous, has frequently been referred to as literature’s “Declaration of Independence,” and was the symbolic beginning of our idea of artists as independent laborers who could depend upon public sales rather than moneyed patronage to support their lives and livelihoods.

Today we see our society moving towards both models at once. Crowdfunding and social media allow artists and makers direct access to their publics on an unpredicted scale — but the erosion of the middle class means that more and more art and arts institutions are increasingly dependent upon the largesse of a new class of ultra-rich patrons.

Burning Man is straddling the crest of both waves. Founded entirely by volunteers and small-scale participant donations in its early years, funded almost entirely by ticket sales in its period of massive growth, it is now perhaps the largest hub for crowd-and-participant funded art in the world. At the same time, it is also famously the new favorite playground of the ultra-rich, who spend ungodly sums of money to do what the rest of us used to do on the cheap.

Anyone who has actually attended Burning Man knows the presence of the 1% in Black Rock City is significantly over-hyped by the media (is anything under-hyped?), and the vast majority of Burners would never know that Richie Rich’s wealthier brother was on playa if people off-playa weren’t complaining about it. But whether it’s causation or correlation, the rise of the 1% at Burning Man does correspond very closely with an increase in the epic scale of the city’s infrastructure, and its art.

As Black Rock City gets bigger, its art has gotten grander — and correspondingly more expensive. To be sure, it is still possible to have profoundly affecting art projects done on a small scale and without permission, but Burning Man has become increasingly associated with the kind of scale and spectacle that requires either a massive crowd-funding campaign or a very wealthy patron.

This is an uncomfortable tension, and maybe unsustainable. It’s also hard to talk about.

Art and money have never been separable, but somehow the idea of talking about them together has become a great taboo. We admire “starving artists” in a way that we would never endorse for “starving teachers” or “starving firemen.” We have a notion deeply embedded in our culture that anybody who talks about doing art for the money must not be a “real” artist. There’s something to that, but it’s also in part a modern concept. It certainly wasn’t Dr. Johnson’s view. He said, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.”

The musicologist Peter Schickele once similarly pointed out, in a hilarious performance that it kills me not to be able to find anywhere online, that most of the correspondence we have of the extraordinarily influential composer Johann Sebastian Bach (a contemporary of Dr. Johnson’s) is not about music at all, but mostly complaining about the cost of living and the fact that his patrons didn’t pay him on time.

(If anyone reading this knows Dr. Schikele, please ask him if he has a clip of that performance we can show.)

So we’ve gone from a period where artists were hyper-aware of money, and open about it, to a period where artists talking about money endangers their status as “artists.” This would be understandable, even laudable, if artists were actually less worried about money, but since they’re not — since in fact we live in a time of profound economic uncertainty about artists and arts funding — this just won’t do.

The 2016 theme of “da Vinci’s Workshop” and Renaissance Florence is intended in no small part to violate this taboo and open this conversation. For the sake of artists, let alone society, we need to think about how we want arts to be funded, how we can do so in ways that are consistent with our values, and how we can create the impact on the arts and funding that we want to have in the world.

To be sure, no one wants to return to the days before Dr. Johnson’s declaration of independence. Leonardo himself illustrates, in his refusal to talk politics, just how stifling that system could be. But not wanting to go back doesn’t mean we can’t learn from history — indeed it’s one of the few things we can learn from. For all its faults, there are many ways in which the Renaissance is exactly what we want to look to for guidance about both what to do and what not to do. If the 21st century is to have patrons, what are best practices for them? How can they be part of the solution, rather than a bottleneck for art and a source of anxiety for artists?

The Renaissance certainly teaches us that there was more than one kind of patron — and more than one reason for making art. While “patronage” today is virtually synonymous with “getting money from a rich guy,” much of the greatest work of the Renaissance was paid for by the church, and many of Florence’s most significant public treasures were paid for by its various guilds. If it was a period every bit as obsessed with money as ours, it was also a period when the most powerful institutions in society saw the creation of art as central to their missions. The glory of God and the state were tied in closely to the art created in their names; a nation or church without public art lacked a fundamental legitimacy. They were not doing their job. Nobility and merchants who did not engage with and support the arts were equally lacking. Money was a means to an end; simply accumulating money served no legitimate social good. Sponsoring art was an alchemy by which money transformed into a higher purpose.

Ironically, we live in an era that claims to value art for its own sake, but that also sees it as far more optional than the Renaissance did. The virulence of a Savonarola against art is only possible when you in fact take art seriously.

Our era has the potential for an unparalleled artistic renaissance. Not only is there plenty of money — if we can only figure out how to access and harness it — but our distribution networks for art and artists are leaps and bounds beyond anything ever envisioned before. We live in a time, to paraphrase Clive James, when it is possible to experience much of the greatest art ever created, for free, without even leaving your home.

Indeed, the ease and quality of the distribution network is part of the problem. Possibly it’s an even greater problem: many societies have tried to address issues of money, equality, and art before, but to my knowledge no society in history has needed to address the problem of art and culture being too easily accessible to everyone. That seems truly a first. It may be, when we dig deep, that some issues of money may not really be about money, much in the way some issues of sex are not really about sex.

But we won’t know until we call them out.

We hope this theme will give Burning Man’s legions of artists, doers, and creative thinkers permission to actively embrace this taboo and a space in which to explore these questions. What can we learn about the relationship between art and money from the Renaissance, and what can we do — what must we do — to embrace the potential of our own time to be the next Renaissance? Hopefully a renaissance as concerned with human dignity and agency as it is with technical advances and artistic accomplishment.

In the series of essays that follow, leading up to the event itself, we will be examining questions that we hope will offer insight and inspiration to anyone looking to address these issues or take on this theme.

Our history, like the histories of those before us, will be defined by our art. Virtually no one remembers Leonardo for his military engineering, but his paintings helped define an era and changed the world. It is a matter of historical record that the only reason anyone really remembers the 4th Earl of Chesterfield today is that Samuel Johnson made fun of him in a letter about an art project that altered the course of civilization.

It may be new technologies and economic forces that make our future possible, but it won’t happen by accident. We need a new Declaration of Independence for artists.

Leonardo, Dr. Landrus tells us, viewed art as a guide to the future. He imagined things that did not exist so that he could build them. So, too, Burning Man: We study the Renaissance in order to imagine a new one. We imagine a new one in order to see if we can build it. In Black Rock City, and around the world.

Re-imagining the relationship between Art and Money, artists and funding, is how we begin.

Coming next: Case studies in being a Renaissance artist

As always an interesting read…

You might find this one of interest…

(it helps to explain the rise of the 1%)

http://paulgraham.com/re.html

Report comment

I stopped reading when I got to this bullshit:

“Anyone who has actually attended Burning Man knows the presence of the 1% in Black Rock City is significantly over-hyped by the media (is anything under-hyped?), and the vast majority of Burners would never know that Richie Rich’s wealthier brother was on playa if people off-playa weren’t complaining about it.”

Report comment

Agreed. Downplaying something that’s patently obvious to anyone who’s been attending for more than five years is a little disingenuous and condescending and smacks of spin.

Report comment

Not only that, but the implication that we should just roll over and accept the FACT of the 1%, which will increasingly become the .5% and the .25%, and figure out how to wring them of their money, is ignoring the central problem. Why not just poll each ticket applicant for their income, and charge $1M/ticket for anyone whose net worth is above $1B, give full grants and stipends to all the artists with the extra money and go back to charging reasonable ticket prices for everyone else? Problem solved!

Any reasonable solution must fundamentally address the greed and power dynamic involved.

Report comment

Lol

Report comment

This article was extremely thought provoking. The patron vs starving artist conflict has compelling pros and cons and there may be no right answer. The one thing that is true is that the lure of money when desperately needed seems justified, but is a slippery slope. Its kind of like your first day ever of calling in sick, its real difficult, but they become cheapened by the first one and are unfortunately easier to do after the first one.

Report comment

No living writer is better suited than you sir to write the 21st Century Declaration of Artist Independence. You blockhead.

Report comment

What happened to the idea of seeing the # of comments on the main page so a reader can determine if there’s anything new without having to click on the article and scroll all the way to the bottom? I had suggested this idea when the blog/journal changes were announced, and as I recall you (or someone else from BM wrote like), but it has not yet been done. I very much appreciate the journal/blog so I’m respectfully repeating my request in case it got lost in the usual shuffle of other stuff in the world.

Report comment

What I’d love to see is more money and free ticket honoraria thingies being given to the small, heartfelt projects that invariably move me at Burning Man. More ducats for sound systems set up in non-thumpa-thumpa music areas of the city.

BRC mirrors everyday American city life in many ways. Over-privileging stuff that costs a vast amount of money doesn’t make B Man super interesting and unique; on the contrary, that’s exactly what dominates our off-Playa lives.

Report comment

Nice writing, Caveat! But you didn’t say HOW this year’s theme brings up this touchy subject. You only point out that Leonardo’s time had patrons and our time has folks with so much money that they choose to drop $250K (the going rate it seems) to have a really great art car!

What I don’t like about these lovely vehicles is that it allows someone who doesn’t even get his/her fingers scuffed to parade around in this piece of art, suggesting that he/she partly made it. I strongly believe that if you present something at bman, you should have at the very least worked hard on, if not designed it entirely.

I know that in the default world rich people commission stuff from artists all the time, but in that world it’s different. When you present some piece of art in your living room, it’s assumed that you DID pay someone to make it.

And in the default world, the ideal is NOT to have the fabulously wealthy choose which art is made by funding and owning it. How can an artist truly explore creativity if he/she is afraid of offending the spigot? It would be far better if the taxes everyone paid were high enough to create an arts organization that could pass out grants to artist chosen by the merits of their proposals! You could call it the National Endowment for the Arts, or something like that! (Yes, we DO have this, but in the post-Reagan era it’s shriveled down to a shadow of its former self.)

Actually, the Burning Man Honorarium system is a quite the scale model of the NEA! It taxes all ticket buyers so that the creation of art can be subsidized. (It’s NEVER paid for in full by the grants.) Burning Man is stuck in the 60s and 70s, and thank god for that!

So no, I don’t appreciate the part of this theme that wants to “celebrate” or “explore” the whole patron-artist relationship. That relationship is poison to artists and brings only pleasant mediocrity to the culture that engages in it.

Report comment

“money changes everything”

Report comment

Tom Wolfe wrote a great essay on the relationship between the bohemian artist, the art critic, and the patron that fits well with this theme. One lasting image was of the starving artists hanging out of their windows in SOHO calling to the limo’s in the streets below, “Pick me. Pick me.”

Report comment

DECOMMODIFY.

motherfuckers.

Report comment

De Vinci would be appalled by all the crap that some consider art at burning man ! He would be more impressed by the naked human form ! He was genius and not wacked out into a disillusioned state of mind !

Report comment

As a professional chainsaw sculptor of near 45 years I too applaud this well written article.

For many playa artists public grants don’t work. BMorg grants only pay for materials and transport costs. I already own my materials…trees are usually “free” to me (Though moving them can be a ball-breaker.) and I live in Carson City, NV, just about an your and a half from the playa… I mean how much gas can it take? But my monuments take months, night and day to create so how to pay bills? (Yep, it’s not really magic, folks…) And what about the inherent politics, favoritism and censorship of ANY public funding platform? These suck the life out of artworks…

These factors have forced me to seek private funding for the production and ongoing expenses of making and schlepping 30′ sculptures to the playa and decoms. Simultaneously though, I’ve been developing what I call an “alternative funding vehicle” for art projects that treats art like the investment it has always been. (More in my web link, just click my name…) I myself am seeking patrons or groups of patrons to take or share ownership of certain of my own “playa artifacts”. These are then shared far and wide in decoms and long-term default installations in public places. Fact is, these showings and “highlights in the public record” (appraiser’s fancy term for mentions and articles in print media…) along with the “provenance” associated with Burning Man and “notoriety” of increasingly prestigious hosting venues make artworks accrue in value!

Caveat Magister I hope you read my link and talk to me dude…we’re on the same page, the time is ripe and I need guidance….

Did I say a bad word? I don’t think so… This article vindicates my years-long efforts and abuses taken by people who many times have never produced an artwork in their lives. This, to create an alternative art funding mechanism based on the investment value of playa art.

PS. Stay tuned for my upcoming blog article on the degrading inequities between BMorg funded playa projects and self-funded playa projects (It gets ugly folks…) Whoops! Did I say another bad word?

Report comment

One thing in today’s (Feb. 3) announcement of 2016 Tickets Info seems germaine to the conversation here – that is, the use of “Leonardo da Vinci” in the tier of “Leonardo da Vinci Art Tickets” being sold at $1200/person

My unease in this use is not squarely because of any particular dollar value. Rather, merely using the name of this (tremendously gifted and influential) person in this particular re-imagining of the relationship of art, money, and the renaissance seems misplaced and like commodification, and it is at least questionable he would have been supportive of the representation, if he were alive today.

I very much hope something else is used :)

http://journal.burningman.org/2016/02/black-rock-city/ticketing/whats-up-with-tickets-for-2016-we-have-answers/

Report comment

I reached out to Mr. Schickele via his website asking if they had the video you talk about in your article. Here is the response:

“I don’t know what performance you’re referring to but there’s very little visual material available on PDQ Bach. The riff about J.S. Bach complaining about money is associated with the Peter Schickele piece, “Bach Portrait,” for narrator and orchestra (the narration consists of quotes from Bach letters complaining about money).

There is no video recording of “Bach Portrait,” but it is on a CD called 1712 Overture and Other Musical Assaults.

There is one DVD called “PDQ Bach in Houston: We Have A Problem,” but I’m afraid it doesn’t have “Bach Portrait” on it.

Good luck and cheers,

Peter Schickele

(dictated to Gregory Purnhagen)”

Report comment

Comments are closed.