At this moment, the people of the Jungle and the police are clashing over evictions. Some men have shown up to protest by sewing their own lips shut with thread. Structures are being set on fire and rocks are being thrown. None of this reflects the Jungle that I visited two short weeks ago, where not once did I feel danger. As I watch the news in Calais — my mind has trouble reconciling the difference between what the media delivers and my experience there.

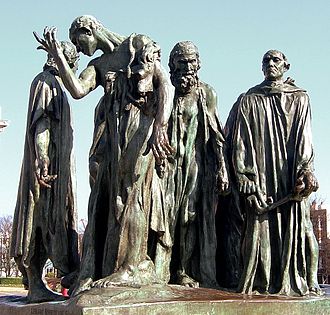

In Calais, France, there is a statue in front of the town Hall. It is the work of Auguste Rodin, called Les Bourgeois de Calais. Six townsmen have been rounded up in 1347 to be executed by Edward III. Pain and uncertainty mark their faces. Not so far away, you can see much the same faces. The difference is that the people are alive. And among them are Burners.

In Calais, France, there is a statue in front of the town Hall. It is the work of Auguste Rodin, called Les Bourgeois de Calais. Six townsmen have been rounded up in 1347 to be executed by Edward III. Pain and uncertainty mark their faces. Not so far away, you can see much the same faces. The difference is that the people are alive. And among them are Burners.

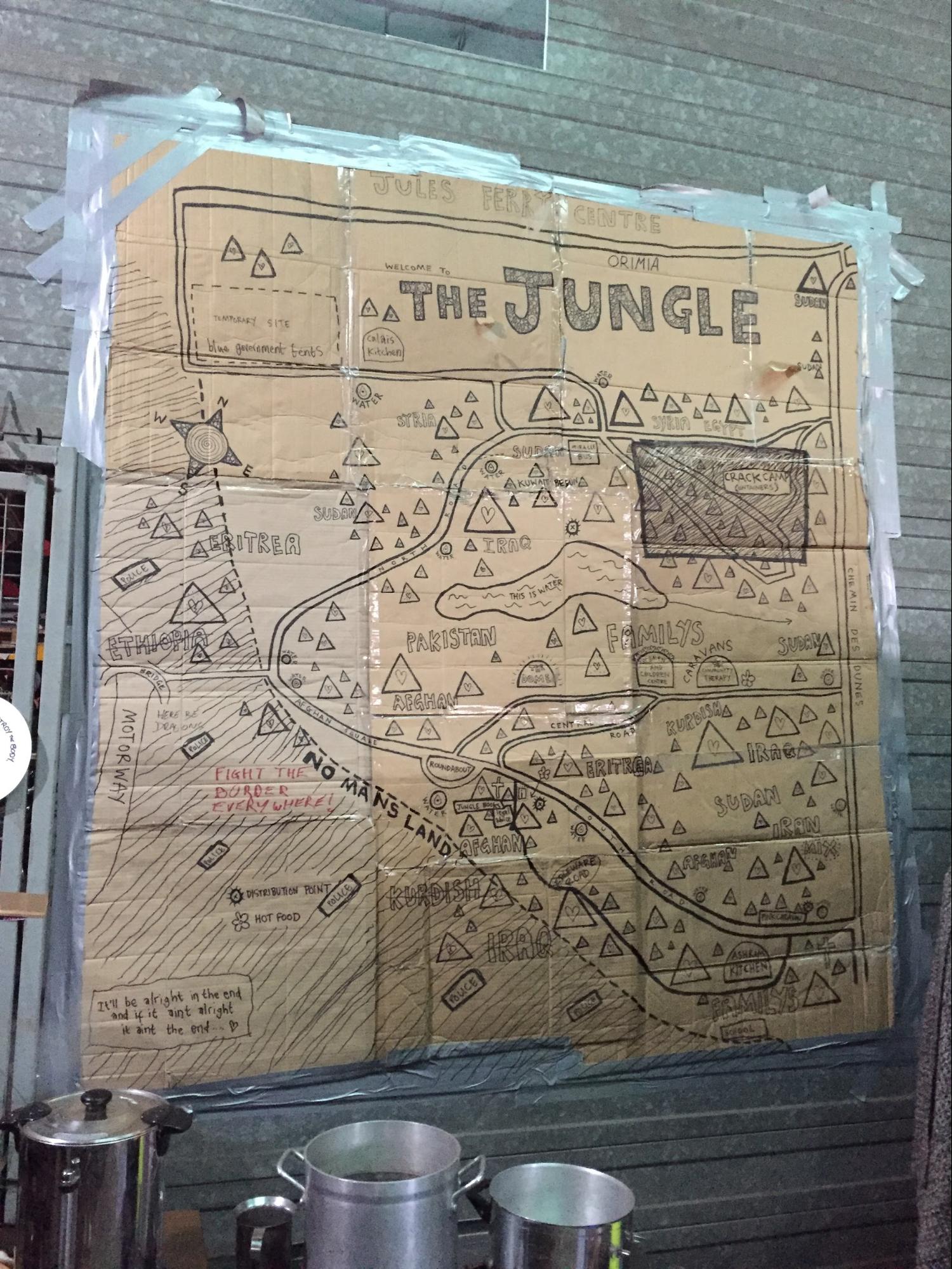

I recently had the opportunity to spend time with the Burners in Calais. They brought me into a sprawling refugee camp known as “The Jungle.” As many as six thousand people live here from countries all across the Middle East and Africa, part of a migration that has brought over one million people into Europe in 2015 alone. They are escaping war, scarcity, poverty and hunger. Mostly, though, they are looking for lives better than the ones they left.

What makes the Jungle remarkable is that it’s an unplanned community where people improvise and create as a means of survival. They are building pre-fab homes, and opening little shops. Since there is nothing official about the place, the government and NGO resources are absent. People fend for themselves, and volunteers fill in the gaps.

So why Calais? It’s the closest you can get to England on the continent. Until recently there was a variety of ways migrants could sneak across. But the landscape of Calais has changed, now permeated by flashing police lights, tall fences and barbed wire.

View a series of graphics compiled by the BBC on the “European Refugee Crisis”

We get a lot of project requests from the Burners Without Borders (BWB) website, but it stands out when multiple projects about the same subject come in within a short time period. This is what happened with The Jungle.

We get a lot of project requests from the Burners Without Borders (BWB) website, but it stands out when multiple projects about the same subject come in within a short time period. This is what happened with The Jungle.

We were already at the Burning Man European Leadership Summit, so it was a perfect time to see it for ourselves. I was joined in this mission by Sarah Poer (Nowhere) & Andy Clutterbuck (Aalto on Fire). Our journey took five days. Maybe it has only just begun.

Upon arriving, we drove to the “secret” warehouse run by L’Auberge (Help Refugees) located about twenty minutes from the camp. The warehouse remains a secret because not everyone in Calais supports the Jungle. Volunteers face pressure from the police as well as variety of militant conservative groups.

The warehouse contains L’Auberge’s donation sorting and distribution center. It is run almost entirely by volunteers, numbering around 50 on the weekdays and up to 200 on the weekends. There is a kitchen, a workshop and caravan housing for the longest-term volunteers. The workshop is responsible for moving refugees from tents into temporary housing, which includes insulation and locking doors — something that’s paramount in keeping people alive and healthy through the cold French coastal winter. Pieces of the structures are pre-fabricated in the warehouse and delivered to people on-site in the Jungle where they assemble the houses themselves. The warehouse is where we met our Burner contact, Kit Johnson.

Kit is wearing a tasseled leather jacket, which he keeps spinning to the amusement of the volunteers. He’s been using the warehouse as his main residence since October and plans on staying. Kit was described to us as “Mr.Fix-it,” and he runs build crews in The Jungle. They build shelters and public structures, and fix the myriad of problems Jungle residents bring every day. The essential gifts he brings goes beyond his building skills however. He has that Burner presence and generosity. Seeing him interact with others makes it clear that his humor and playfulness lift the spirits of the people he’s around. At the moment Kit is joined by Charlie Richardson (Nowhere), Ian Beaverstock (Temple of Transition) and Jayne Davidson (Mazu Temple).

The Jungle is three miles outside the city center, located on an old landfill. Moving past the police vehicles, you enter the camp into a scene that’s too familiar in our world: a muddy shanty town. Yet there’s quite a bit more. Volunteers have been building a variety of assets including a women’s center, a vaccination center, school, library, and even a playground. These resources are staffed each day by dedicated volunteers, many of them from the UK. They confess a sense of shame from the lack of response by their own government.

The Jungle is three miles outside the city center, located on an old landfill. Moving past the police vehicles, you enter the camp into a scene that’s too familiar in our world: a muddy shanty town. Yet there’s quite a bit more. Volunteers have been building a variety of assets including a women’s center, a vaccination center, school, library, and even a playground. These resources are staffed each day by dedicated volunteers, many of them from the UK. They confess a sense of shame from the lack of response by their own government.

Traveling deeper into the camp, you find a surprising amount of infrastructure amidst the rumbling generators and drainage ditches. The feel is distinctly urban and grassroots at the same time. There’s a village being built here. There are two “commercial streets” which consist of resident-run businesses. These include restaurants, cafés, barbershops, a bath house, bars, a mosque, a church and corner stores. The people here aren’t poor — there’s money to be traded. They are stuck not in poverty, but in politics.

One of the most inspiring structures was the “Good Chance” theater, created by two English playwrights who came to the Jungle to find a story. After spending time here, they realized that it wasn’t their job to take a story out of the Jungle, but to create a space inside the Jungle where all sorts of stories could be told. They decided to build a dome in the camp to house the theater. It has become a public commons, a place for workshops, theater shows and movies. It’s had more migrant-led workshops as time goes on, and even offers residencies to artists. The Good Chance is a place where you can see arts, civic space, volunteering, and humanitarian aid all converging into impact and meaning.

The thing about a Jungle is that it’s wild and always changing. Recently, a large section of camp was bulldozed for the “container camp.” These containers are the French government’s attempt at a longer-term solution. Unfortunately, the containers are devoid of life, in part because of the requirement that people give over their biometric data to enter them, barring them from receiving asylum in the UK once they’ve registered with the French government. The containers sit almost empty in stark contrast to the camp that surrounds them.

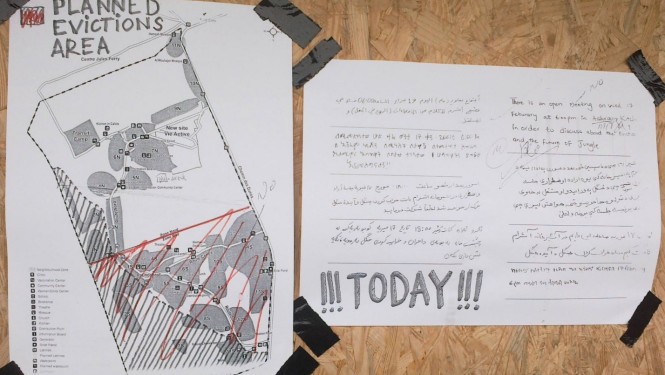

Our project had been to create a second structure for the “Baloos Youth Center” that would house a punching bag and other activities for the kids. The first few days were spent building the frame, and our last day was about putting down the floor. Halfway through laying the foundational pallets, news started to circulate around the camp, and the energy shifted and became static: In 1-2 weeks time, the French government would bulldoze the southern half of camp. This area included somewhere between 1,000 and 3,000 people’s homes and most of the established infrastructure. The kitchen, the theater, the women’s center, and even the youth center that we were so close to finishing.

The hardest part of the trip wasn’t seeing the physical conditions people lived in, but rather the uncertainty. The uncertainty of tomorrow. The uncertainty of whether their homes would be bulldozed or spared. The uncertainty of how much waiting would has to be done and if the dream of England would ever materialize. No one meant to end up in the Jungle, they’re just stuck here. The beauty in a temporary society — the heartbreak at the lack of a real and humane solution.

It’s the dynamism of this community that is its strength. It allows the people to make their seemingly unlivable conditions livable. Yet the institutional reaction to communities like this (when they’re even acknowledged) seems to squelch that dynamism — to make these people sit down and shut up — and this doesn’t actually help at all. It echoes the pain on the faces of a statue sculpted by Rodin over 600 years ago about people living in that same coastal town.

It shouldn’t be a surprise by now that when you drop into some of the most difficult and complicated situations on earth, you find Burners, and they’re prototyping solutions. Our community seems to attract those who are willing to take chances and live on the edge with a passion to attempt the creation of a better world. We seem to have the skills to survive in adverse conditions, people who can build, manage, roll with the punches, and find gaps in the social structure while having the leadership to bring about creative and immediate solutions.

Whether you go to the Jungle, to Lesvos, or to Germany, you are bound to find Burners working on solutions to the crisis. We’re planning on having more reports from our friends working in these places to let us know what they see first hand and ways we can get involved.

To appropriate a phrase: “If you see something, say something.” The person who hears you may be just the person you need.

I think that Sarah Poer’s reaction to the news of the planned destruction for the south end of the Jungle may just summarize all of our feelings towards the end. Take a look:

Follow these links to explore The Jungle for yourself:

Hey, how can we help with this project? What do the team need help with?

Report comment

Elizabeth. Feel free to email me at:

breedlove@burningman.org

I’m happy to provide more information and places you can become involved.

Report comment

Wow. This is what keeps me in the Burner community. Thank you.

Report comment

Thank you Chris for this article and to all the amazing people doing what they can to help those in need!

We (myself and documentary film maker / burner Oskari Pastila) will return next week to continue the story, hoping to find ways to communicate effectively and responsibly to those wanting to help. Guiding the help towards those that organise and distribute the support, people that are as professional and talented as they are big hearted.

Report comment

Thank you.

Report comment

compassion driven by creative action thanks for sharing this story and perspective <3

Report comment

Amazing I never met you on your visit. I’m a fellow burner, check out what we’re up to:

https://crowdfunding.justgiving.com/Noproblem

Report comment

Comments are closed.